Presentación del libro de Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011

“I was twenty years behind the Times”

(Ezra Pound, ‘Contemporania’, 1913)

Masa y Poder: Ezra Pound pedagogo

Por Nicolás González Varela

http://geviert.wordpress.com

“GUÍA DE LA CULTURA. Título ridículo, truco publicitario. ¿Desafío? Guía debería significar ayuda a otra persona a llegar a un sitio. ¿Debemos de despreciarlo? Tiros de prueba.”[1] El único libro del economista-poeta Ezra Loomis Pound que salió en el annus memorabilis de 1938[2] fue una anomalía desde todo punto de vista. Su título: Guide to Kulchur (GK). En sus páginas puede disfrutarse del mejor Pound vanguardista, que como Minerva nace armado con su método ideogramático, un Pound sin temor ni temblor a fundir en una nueva síntesis, en una Summa de su pensamiento, nada menos que a Jefferson, Mussolini, Malatesta, Cavalcanti y Confucio. Pound vive en la Italia fascista desde fines de 1924, ha vivido la consolidación, estabilización y maduración del regimen fascista, desde cuyas fórmulas políticas e instituciones económicas, cree con fervor, puede plantearse una terza via entre el capitalismo liberal en bancarrota y el socialismo burocrático de Stalin. También son los años en que Pound, demostrando su estatura intelectual, pasa de las preocupaciones estéticas a las éticas. El libro tiene su propia historia interna, una poco conocida tortured history: en febrero de 1937 Pound inicia una correspondencia con el playful in-house editor Frank Morley (a quién Pound llamaba cariñosamente por su tamaño Whale, ballena), de la editorial inglesa Faber&Faber. Pound le informa acerca de un nuevo libro revolucionario de prosa. Estaría muy bien, le contestaba Morley, que en lugar de escribir algo similar a su ABC of Reading, de 1934, publicara sus ideas sobre lo que entiende por la Cultura con mayor extensión y profundidad. Inmediatamente Pound le contesta que pensaba en primer lugar en una obra que se llamaría The New Learning (El nuevo Aprendizaje), luego sugirió el nombre de Paideuma, pero desde el principio el editor Morley lo consideraría, más que como un Hauptwerk exhaustivo sobre el tema, como una introducción o guía, por lo que surgió el nombre de Guide to Cultur, que llevaría un subtítulo curioso luego desechado “The Book of Ezro”: “un libro que pueda funcionar como una educación literaria para el aspirante a todas las excavaciones y que desea hacer volar el mundo académico antes que hacer su trabajo.”[3] Morley además le aseguraba que para un popular textbook como del que hablaba, existía un amplio mercado potencial de lectores. En una carta dirigida al editor Pound en febrero de 1937 describía el proyecto como “lo que Ez (Ezra) sabe, todo lo que sabe, por siete y seis peniques” (y en tamaño más portable que el British Museum)[4], y le explicaba que introduciría algunos contrastes entre la decadencia de Occidente y Oriente y que también mencionaría los aspectos “raciales” de la Cultura. Además describía el esqueleto de su futura obra en tres grandes bloques: I) Método (basado en las Analectas de Confucio); II) Filosofía (en tanto una exposición y a la vez crítica de la Historia del Pensamiento) y III) Historia (genealogía de la acción o los puntos cruciales del Clean Cut).[5] Finalmente se firmó el contrato formal entre ambas partes y el libro se denominaba en él como Ez’ Guide to Kulchur.

GK fue publicada entonces por la editorial Faber&Faber[6] en el Reino Unido en julio de 1938 y por la editorial New Directions, pero bajo el título más anodino de Culture, en noviembre de 1938 en la versión para los pacatos Estados Unidos. Pound la escribió de corrido en un mes durante la primavera de 1937 (marzo-abril), bajo un estado anímico al que algunos biógrafos como Tytell denominaron “a sense of harried desperation”.[7] Como saben los que conocen su vida y obra, cada movimiento que propugnaba lo tomaba como un asunto de emergencia extrema y límite. Según el irónico comentario del propio Pound “el contrato de la editorial habla de una guía DE la cultura no A TRAVÉS de la cultura humana. Todo hombre debe conocer sus interioridades o lo interno de ella por sí mismo.” y efectivamente no defraudó a sus editores en absoluto. El libro (si podemos denominarlo así) era un escándalo antes de ver la luz. Aparentemente nadie de la editorial leyó en profundidad el manuscrito en su contenido polémico y cercano al libélo. Ya había ejemplares encuadernados, listos para entregar al distribuidor, cuando la editorial inglesa Faber&Faber decidió que, posiblemente, algunos pasajes eran radicalmente difamatorios. Al menos, según cuentan especialistas y biógrafos confiables, se arrancaron quince páginas ofensivas, se imprimieron de nuevo y se pegaron con prisa; también se imprimieron nuevos cuadernillos de páginas para los ejemplares que no habían sido encuadernados todavía.[8] No nos extraña: sabemos que Pound como crítico “jamás experimentó el temor de sus propias convicciones”, en palabras de Eliot. Quod scripsi scripsi. Lo extraño y maravilloso es que el libro como tal haya sobrevivido a semejante desastre editorial. GK fue finalmente publicado el 21 de julio de 1938, estaba dedicada “A Louis Zukofsky y Basil Bunting luchadores en el desierto”. Zukofsky era un mediocre poeta objetivista neyorquino, autodefinido como communist, al que Pound adoptó como discípulo y seguidor de sus ideas[9]; a su vez Bunting era un poeta británico, conservador e imperialista, que Pound ayudó con sus influencias intelectuales y el mecenazgo práctico.[10] Pound mismo consideraba GK, circa 1940, como la obra en la que había logrado desarrollar su “best prose”[11], además la ubicaba, junto a The Cantos, Personae, Ta Hio, y Make It New, en el canon de sus opera maiorum. También lo consideraba uno de sus libros más “intensamente personales”, una suerte de ultimate do-it-yourself de Ezra Pound. Su amigo, el gran poeta T. S. Eliot afirmó que tanto GK como The Spirit of Romance (1910) debían ser leídos obligatoriamente con detenimiento e íntegramente. Aunque puede considerarse el más importante libro en prosa escrito por Pound a lo largo de su vida[12], sin embargo Guide to… no cuenta con el favoritismo de especialistas y scholars de la academia (a excepción de Bacigalupo, Coyle, Davie, Harmon, Lamberti, Lindberg y Nicholls).[13] El mejor y más perceptivo review sobre el libro lo realizó su viejo amigo el poeta Williams Carlos Williams, en un artículo no exento de críticas por sus elogios desmesurados a Mussolini titulado “Penny Wise, Pound Foolish”. En él, Williams señalaba que a pesar de todas su limitaciones o errores involuntarios, GK debía ser leído por el aporte de Pound en cuanto a revolucionar el estilo, por su modo de entender la nueva educación de las masas y por iluminar de manera quirúrgica muchas de las causas de la enfermedad de nuestro presente.[14] En cambio nosotros no consideraremos a GK ni como un libro menor, ni como un divertido Companion a su obra poética, ni como un torso incompleto, ni siquiera como un proyecto fallido. En realidad GK es una propedeútica al sistema poundiano, su mejor via regia, un acceso privilegiado a lo que podríamos denominar los standard landmarks[15] de su compleja topografía intelectual: la doctrina de Ch’ing Ming, el famoso método ideogramático, su libro de poemas The Cantos entendido como un tale of the tribe, la figura de la rosa in steel dust,[16] la forma combinada de escritura paratáctica[17], el uso anti y contrailustrado de la cita erudita, su deriva hacia el modelo fascista (la economía volicionista y su correspondiente superestructura cultura)[18], la superioridad en el conocimiento auténtico de la Anschauung[19] como ars magna y el concepto-llave de Paideuma. GK puede ser además considerado un extraordinario postscript a su opera maiorum, hablamos de la monumental obra The Cantos, en especial a los poemas que van del XXXI al LI, publicados entre 1934 y 1937. Pound se propone incluso romper con su propia prosa pasada: “Estoy, confío de manera clara, haciendo con este libro algo diferente de lo que intenté en Como leer, o en el ABC de la Lectura. Allí estaba tratando abiertamente de establecer una serie o un conjunto de medidas, normas, voltímetros; aquí me ocupo de un conjunto heteróclito de impresiones, confío que humanas, sin que sean demasiado descaradamente humanas.”[20]

US propaganda contra la cultura alemana, I Guerra

En primer término, y por encima de todo, debemos señalar al lector ingenuo que Ezra Loomis Pound ha sido un pedagogo y un propagandista antes que nada y se propone nada más ni nada menos que GK sea un Novum Organum, al mejor estilo baconiano[21], de la época incierta que se abre ante sus pies. Llamarlo Kulchur tiene su explicación filosófica y política: Pound quería referirse al concepto alemán de Cultura (Kultur) pero para diferenciarlo del tradicional que utiliza la élite (irremediablemente lastrado de connotaciones clasistas, nacionalistas y raciales), lo escribe según la pronunciación; y al mismo tiempo anula la indicación tradicional que tiene el concepto Cultur en inglés. Este sesgo nuevo y revolucionario a lo que entendemos en la Modernidad por Cultura es el primer paso para la tarea de un New Learning de masas y la posibilidad histórica de un nuevo Renacimiento en Europa, ya que “las democracias han fallado lamentablemente durante un siglo en educar a la gente y en hacerle consciente de las necesidades totalmente rudimentarias de la democracia. La primera es la alfabetización monetaria.” Su significado temático revolucionario, intentar comprender de otro modo al Hombre, la Naturaleza y la Historia, debemos señalarlo, excede el mero ejercicio de escribir poesía. Es una vigorosa reacción contra la Aufklärung, que para Pound es una período de lenta decadencia, la verdadera Dark Age de Occidente, signado por la subsunción de toda la Cultura a la usura y el mercantilismo más brutal (institucionalizados en una forma perversa: la banca): “Hemos ganado y perdido cierto terreno desde la época de Rabelais o desde que Montaigne esbozó todo el conocimiento humano.”[22] Como Nietzsche, Pound rescata de las Lumiéres tan solo a Bayle y Voltaire y si Nietzsche intentó este nuevo desaprendizaje-aprendizaje contra la Modernidad desde la forma literario-política del aforismo, Pound lo intentará desde el ideograma y el fragmento citacional, buscando el mismo efecto pedagógico en las masas, en el hombre sin atributos, que había experimentado en persona en la Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista[23] inaugurada en el Palazzo delle Esposizioni de Roma en 1932.

¿El libro es en realidad un enorme ideograma de acceso a la verdadera Kulchur? Recordemos que para Pound Cultura con mayúsculas es cuando el individuo ha “olvidado” qué es un libro, o también aquellos que queda en el hombre medio cuando ha olvidado todo aquello que le han enseñado.[24] Y que entonces de alguna manera la auténtica Cultura se correlaciona con una forma privilegiado de relación entre el sujeto y el objeto, la Anschauung, opuesta sin posibilidad de cancelación con el Knowledge de la Modernidad, un producto amnésico y totalitario (en sentido gestáltico, no político) prefabricado a través de un enfoque deficiente de el Arte, la Economía, la Historia y la Política. La Anschauung es superior, tanto epistémica como políticamente: “La autoridad en un mundo material o salvaje puede venir de un prestigio acumulado, basado en la intuición. Confiamos en un hombre porque hemos llegado a considerarle (en su totalidad) como hombre sabio y bien equilibrado. Optamos por su presentimiento. Realizamos un acto de fe.”[25] Siempre hay que subrayar que Pound no tiene como propósito exclusivamente el regodeo narcisista de transmitir “descubrimientos”, ni progresar en algún tipo de carrerismo académico, sino que su pathos radical presionaba a que sus tesis deben ser llevadas a la práctica, y por ello él mismo nos muestra el camino y custodia con celo la senda adecuada para tal traducción material: “Y al llegar aquí, debemos hacer una clara diferencia entre dos clases de «ideas». Ideas que existen y/o son discutidas en una especie de vacío, que son como si fueran juguetes del intelecto, e ideas que se intentan poner en «acción» o guiar la acción y que nos sirven como reglas (y/o medidas) de conducta.”[26] La distinción de Pound fijada en el concepto técnico de “Clean Cut” entre ideas in a vacuum y las ideas in action (básicas como reglas de conducta) es crucial en este sentido.[27] Pound decía que al final GK no era más que “su mapa de carreteras, con la idea de ayudar al que venga detrás a alcanzar algunas pocas de las cimas, con menos trabajo que el que uno ha tenido…” Para lograr una educación profunda y postliberal, decía Pound que el alumno debía dominar las siguientes bases mínimas: todo Confucio (en chino directamente o en la versión francesa de M. G. Pauthier), todo Homero (en las traducciones latinas o en la francesa de Hughes Salel), Ovidio, Catulo y Propercio (utilizando como referencia la Metamorfosis de Golding y los Amores de Marlowe), un libro de canciones provenzales (que al menos incluya a los Minnesingers y a Bion), por supuesto Dante (además treinta poemas de sus contemporáneos, en especial de Cavalcanti), “algunos otros temas medievales… y algún esbozo general de la Historia del Pensamiento a través del Renacimiento, Villon, los escritos críticos de Voltaire (incluyendo una pequeña incursión en la prosa contemporánea), Stendhal, Flaubert (y por supuesto los hermanos Goncourt), Gautier, Corbière y Rimbaud.”[28] GK es la Guía Baedeker, que puede superar en un solo mandoble las limitaciones tanto de la Modernidad liberal como el Comunismo de sello staliniano[29], a través de una nueva genealogía basada en lo que denomina the Best Tradition, o en palabras de Pound “En lo esencial, voy a escribir este nuevo Vademécum sin abrir ningún otro volumen, voy a anotar en la medida de lo posible solamente lo que ha resistido a la erosión del tiempo y al olvido. Y en esto hay un poderoso argumento. Cualquier otro camino significaría que me vería obligado a tener que citar un sinnúmero de historias y obras de referencia.”[30]

El primer efecto del método poundiano en el lector ingenuo y tradicional es la desorientación en el maremagnum de las yustaposiciones y la interrupciones en la ilación lógica. Además es evidente que Pound “juega” con el diseño gráfico de la página, trasciende la linearidad del texto, subvierte las normas establecidas de signos y morfología, trascendiendo el contenido a través de imágenes: reproducción de ideogramas, partituras musicales, fragmentos citacionales de temas diversos, citaciones ad verbatim, déjà-vus semánticos, formas coloquiales anónimas et altri. Esto efectos no son meramente buscados en busca de algún efecto visual “vanguardista”, “lúdico” o “creativo”, en absoluto (aunque co-existan en GK como efectos de composición) sino de crear un nuevo soporte, mitad estilo mitad icónico, capaz de vehicular, de soportar como medio comunicativo eficaz, la nueva sensibilidad que reclama Occidente en decadencia: “El lector con prisas puede decir que escribo en clave y que mis afirmaciones se deslizan de un punto a otro sin conexión u orden. La afirmación es, sin embargo, completa. Todos los elementos están ahí, y el más perverso de los aficionados a los crucigramas debería ser capaz de resolverlo o de verlo.”[31] Pound reclama en GK su idea de One-Image Poems, paradigma poético-icónico, o incluso podemos llamarlo una suerte de “lenguaje mosaico”, que como hemos señalado, se eleva sobre el sólido fundamento de la yuxtaposición paratáctica de texto e imágenes diversas, creando una suerte de espacio acústico.[32] El aspecto formal del método ideogramático es muy importante para Pound, y uno de sus componentes centrales es su propia definición de imagen como una presencia compleja que implica tanto lo intelectual como lo puramente emocional en una simultaneidad: “an Image is that which presents an intellectual and an emotional complex in an instant of time.”[33] Una definición totalmente bergsoniana: la inmediata, la interacción intuitiva inmediata con la imagen, el mismo instante del tiempo en que esta interacción se produce, el espontáneo crecimiento formativo por la presencia del élan vital, el retorno a los horned Gods y la libertad total con respecto de los límites “normales” que determinan el cuadro perceptivo burgués, tienen directa contraparte con el concepto de evolución creadora de la filosofía de Henri Bergson.

GK es concebido por Pound para las grandes masas, el gran público amorfo de la infernal sociedad industrial-mercantilista[34], el despreciado uomo qualunque, al cual el poeta intenta re-educar en un modo revolucionario, polémico y de mortal enfrentamiento con el sistema institucional y académico burgués y para sobrevivir a la sobre información generada por la opinión pública moderna: “Estoy, en el mejor de los casos, tratando de suministrar al lector medio unas pocas herramientas para hacer frente a la heteróclita masa de información no digerida con que se le abruma diaria y mensualmente, y lista a enmarañarle los pies por medio de libros de referencia.”[35] La hipótesis no explícita de Pound es el reconocimiento de la irrupción irreversible en la Historia de una nueva “masa”, heterogénea y segmentada (aunque tanto el tardoliberalismo como el burocratismo soviético intentarán homogeneizarla y uniformarla), que empuja a revisar axiomas y arcani imperii consolidados: estado, economía, política, cultura, organismo social, poder. Es a esta masa, que soporta el efecto reaccionario de los new media, es el objeto privilegiado de intervención al que se dirige GK con la ideología a la que adhiere Pound, tanto en lo personal (las nuevas teorías económicas de Gesell, el confuso antisemitismo)[36] como en lo corporativo (el Stato totale de la Italia fascista como anticipación)[37]. El método ideogramático se coloca así como una refinadísima actividad de agitprop, con la capacidad de retomar fuentes de la tradición culta (consciente y críticamente seleccionadas)[38], elementos literarios como la voz y la autoridad autoral (que le otorga credibilidad e identidad al texto), para refundirlos con los nuevas necesidades de consenso y reproducción que han generado en el sustrato popular los nuevos medios de comunicación (¡de masas!) de la esfera pública burguesa, así como las modalidades de consumo y ocio. Y es por ello la importancia hoy de volver a leer GK como un laboratorio que lleva a sus límites la propia Weltanschauung tardomodernista, en esa experimentación entre desarrollo formal y la voluntad de generar nuevos “efectos” que van más allá de lo meramente poético en el uso de herramientas retóricas.

Pound persigue regenerar un Total Man, pero revulsivo y de signo inverso al de la ideología demo-liberal, que puede realizar una conversión y metamorfosis de tal magnitud que le permita “conversar” con los grandes filósofos y generar buenos líderes. Esta “regeneración”, por supuesto, es incompleta y unilateral si no se logra que los vórtices del Poder y los vórtices de la Cultura coincidan[39], por lo que la efectividad de GK sólo podrá verse reflejada cuando la forma estado en Occidente tienda hacia el Stato totale[40] de la Italia fascista. Y del elemento corporativo deberían aprender con humildad las deficientes y corruptas democracias liberales, en especial Reino Unido y los Estados Unidos de América, ya que “NINGUNA democracia existente puede permitirse el pasar por alto la lección de la práctica corporativa. El ‘economista’ individual que trate de hacerlo, o bien es un tonto o un sinvergüenza o un ignoramus.” En otro polémico libro, Jefferson and/or Mussolini, Pound lo describe de esta manera: “Un buen gobierno es aquel que opera de acuerdo con lo mejor de lo que se conoce y del pensamiento. Y el mejor gobierno es el que traduce el mejor pensamiento más rápidamente en acción.”[41] De igual manera lo expresa mucho más pristínamente en GK: “El mejor gobierno es (¿naturalmente?) el que pone a funcionar lo mejor de la inteligencia de una nación.”[42] Es esa simultaneidad expresada en un Best Government es la que abrirá la puerta en Europa a un nuevo Renacimiento, a una Era of Brillance libre de la Ley del valor capitalista (explotación) y de su efecto más funesto: la usura: “Si el amable lector (o el delegado a una conferencia internacional económica de U.S.A.) no puede distinguir entre su sillón y la orden de un alguacil, que permita a este último secuestrar dicho sillón, entonces la vida le ofrecerá dos alternativas: ser explotado o ser más o menos alcahuete, mimado por los explotadores, hasta que le llegue el turno de ser explotado.”[43] La nueva Kulchur debería ser una arma masiva y práctica contra la explotación, una arma que trasciende tanto la burocrática proletarskaya kultura de la URSS como la falsa meritocracia del sistema demo-liberal anglosajón, cuya alma oculta es el mecanismo de la usura. La usura, un tema omnipresente en la obra de Pound, es definida en su libro The Cantos, en una nota bene al canto XLV como: “Usura: gravamen por el uso del Poder adquisitivo, impuesto sin relación a la producción, a veces sin relación a las posibilidades de la producción (de ahí la quiebra del banco de los Medici)”.[44] Para Pound, como para muchos intelectuales no-conformistas de los 1930’s, el mundo se dividía, no en proletariado y capitalistas, sino en una peculiar lucha de clases entre productores y usurers. La única posibilidad epocal de superación de este estado contra naturam del hombre, dominado por el finance Capitalism, era la coincidencia de la Paideuma con un regimen autoritario-corporativo. Y para ello era necesario un salto en la conciencia de las masas por medio de una acción pedagógica militante. Pound siempre sostuvo un compromiso con los temas educativos y una pasión vocacional por la pedagogía, hasta tal punto de planificar literary kindergartens. Se podría decir que GK es un esfuerzo más en el ideal de una sociedad basada en un nuevo aprendizaje y en medios educativos revolucionarios.

Merece un párrafo su especial relación intelectual ambivalente con Karl Marx, del cual pueden verse rescoldos en GK. La formación económica de Pound se realizó íntegramente a través de de economistas heterodoxos, algunos importantes aún hoy en día, como el economista anarquista Silvio Gesell (discípulo de Proudhon) y otros que han pasado al justo olvido, como C. H. Douglas u Odon. Ya en pleno fascismo italiano Pound dio conferencias sobre economía planificada y la base histórica de la economía en la Universidad de Milán a partir de 1933. Al inicio del ‘900 en sucesivos artículos Pound defiende las reformas socialistas llamadas Social Credit, en clave proudhonnistes y sus economistas de cabecera es siempre Douglas y Gesell, de quienes decía habían lograda acabar con the Marxist era. Como muchos pre fascistas, Pound cree que modificando la esfera de la circulación y la distribución podría nacer una nueva sociedad sin tocar las estructuras sociales y políticas, sin tocar el derecho de propiedad básico. El Fascismo es el único, entre el Comunismo y el detestable capitalismo liberal, de llevar a buen término, la justicia económica. Pound se percibe con muchas afinidades con Marx, valora su figura de social Crusader, alaba la noble indignación tal como surge en la retórica de Das Kapital, sabemos que Pound pudo leerlo en traducción italiana, pero una indignación que sin embargo es como una nube que confunden al lector. Además Marx esta en una siniestra genealogía filonietzscheana que desde la Ilustración radical desemboca en una nueva forma de décadence. Para Pound la verdad de lo que denomina Marxism materialist está en sus resultados prácticos en Lenin y Stalin, en la burocracia soviética y el Gulag: “El fango no justifica la mente. Kant, Hegel, Marx terminan en OGPU. Algo faltaba.”[45] Pound también comparte con Marx que las relaciones económicas materiales son fundamentales para la comprensión exacta de la dinámica social, y adhiere completamente a la crítica de la avaricia y la crueldad del British industrialism. Siguiendo en esto a Gesell, Pound cree que el Marxismo qua ideología fijada en un estado en realidad no significa ningún desafío al capitalismo liberal, al bourgeois demo-liberal: “Los enemigos de la Humanidad son aquellos que fosilizan el pensamiento, esto es lo MATAN, como han tratado de hacerlo los marxistas en nuestra época, lo mismo que un sin número de tontos y de fanáticos han tratado de hacerlo en todos los tiempos, desde la cadencia musulmana, e incluso antes. HACEDLO NUEVO”[46] La doctrina de Marx murió en 1883, el mismo día de su muerte: solo quedan sus acólitos construyendo un nuevo y esclerótico dogma. Del mismo Gesell, Pound tomará acríticamente su endeble crítica a la teoría de la moneda y de la ley del valor marxiana. Por ello Marx jamás podrá dañar definitivamente al Capital: “El error de la izquierda en las tres décadas siguientes fue que querían usar a Marx como el Corán. Supongo que la verdadera apreciación, esto es, el verdadero intento de apreciar el mérito verdadero de Marx empezó con Gesell y con la afirmación de Gesell de que Marx nunca ponía en duda el dinero. Lo aceptó buenamente tal como lo encontró.”[47] Sabemos que sus conocimientos de Marx son pocos y fragmentados, centrados literariamente en el capítulo VIII de Das Kapital, que se ocupa de la lucha por la jornada laboral.[48]

¿Podía calificarse a Pound de nietzscheano? Aunque se discute si existe algún elemento de nietzscheanismo difuso en Pound, es evidente que conceptos-llave de su Weltanschauung, están derivados o de Nietzsche o de seguidores, inclusive el mismo término Paideuma acuñado por Frobenius está inspirado en última instancia de un nietzscheano radical auténtico como Oswald Spengler. Se puede hablar de afinidades electivas y de influencias indirectas del Nietzschéisme en la conformación del paradójico Aristocratism side del individualismo metodológico de Pound sin lugar a dudas.[49] Pound ya utilizaba terminus technicus nietzscheanos, como Over Man (Superhombre) a inicios del ‘900, aunque producto de una lectura fragmentada y a tirones, o como él mismo confesaba en un poema I believe in some parts of Nietzsche/I prefer to read him in sections.[50] Incluso llega a aceptar como válida las consecuencias biológicas de la filosofía de Nietzsche y su oposición intransigente a toda conclusión cooperativa o colectivista: “I, personally, may prefer the theory of the dominant cell, a slightly Nietzschean biology, to any collectivist theories whatsoever.”[51] En un poema-funerario dedicado a su admirado amigo Gaudier-Brzeska titulado “Reflection”, Pound hace otro acto de fe hacia Nietzsche: “I know what Nietzsche said is true…”[52] La afinidad electiva es más que obvia, los une pasión pedagógica y una hybris reactiva: Nietzsche también estuvo obsesionado por la Paideia como base del estado, por la cuestión formativa y las reformas educativas que pudieran detener la decadencia burguesa de Occidente.[53] También como en Nietzsche, como en Mann o como en Heidegger, Pound sostiene la creencia que el stress de los costos extras de la dominación burguesa, que implica la constante revolución de las fuerzas productivas y el avance tecnológico, es insostenible, decadente y alienante. Coexisten en Pound el interés por la alta o nueva tecnología con el pesimismo sobre la interrupción vital de la fluidez de la imaginación, la negra posibilidad de la hegemonía del hombre sin atributos y sus consecuencias en la Cultura. Es la típica ambivalencia ideológica del Modernismo a la que no escapa Pound: mientras la techné es celebrada como una extensión proteica de la voluntad de poder del hombre en la máquina, el efecto total debido a la forma de dominio bourgeois es ácidamente atacada como una totalidad falsa, despersonalizada, inauténtica y vacía. Contra este gigantesco movimiento milenario de decadencia y empobrecimiento es que Pound levanta su New Learning, su revolucionaria Guía a la Cultura, y por ello afirma sin hesitar que sus ojos are geared for the horizon.[54]

La obra de Pound tanto poética como en prosa es difícil o de imposible lectura, decía sabiamente Borges, aunque reconocía la obligatoriedad de su lectura, ya que con él la literatura norteamericana y la ensayística universal había tocado las alturas más temerarias. Invitamos al lector al desafío de sumergirse en uno de las mejores ensayos del siglo XX, ahora disponible en una exquisita edición crítica y completa.

[1]Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 195.

[2] En su Guide to… Pound coloca la fecha exacta de su urgente escritura: “16 de marzo anno XV Era Fascista”. Desde 1931 Pound utilizaba el nuevo calendario fascista. Los biógrafos creen que la ansiedad de Pound se debía a las consecuencias inmediatas de la crisis de Münich, el Tratado de Rapallo y la posibilidad de una guerra europea catastrófica. No estaba equivocado en absoluto.

[3] Morley le afirmaba que “seeryus & good sized home university library for the seeryus aspiring & highminded youth… a book that would function as… litry education for the aspirant with all the excavations you wish blowing up what it is the academics do instead of their job.”, en: Pound Papers, February, 1937, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven, Connecticut; parcialmente on-line: http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/digitallibrary/pound.html

[4] Pound decía: “Wot Ez knows, or a substitute (portable) fer the Bruitish museum”, en: ibidem, February, 1937. Lo de “Bruitish” una ironía bien poundiana.

[5] Un esquema básico que mantendrá en GK: “Ningún ser viviente sabe lo suficiente para escribir: Parte I. Método; Parte II. Filosofía, la historia del pensamiento; Parte III. Historia, o sea, la acción; Parte IV. Las Arles y la Civilización.”, en: Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 57.

[6] La editorial Faber fue la editorial en inglés más importante en la difusión de la entera obra de Pound, llegando a editar más de veinte títulos entre 1930 y 1960; en ella trabajaba como primary literary editor su amigo, el poeta T. S. Eliot.

[7] Tytell, John; Ezra Pound: The Solitary Volcano, Anchor P, New York, 1987, p. 247.

[8] Stock, Noel; Ezra Pound; Edicions Alfons El Magnànim, Valencia, 1989, p. 441 y ss. Pound conservó como un tesoro cinco ejemplares de GK no expurgados. Lo señala también Gallup en su definitiva obra bibliográfica: Gallup, Donald; A Bibliography of Ezra Pound. 1963, edición revisada y ampliada: Ezra Pound: A Bibliography, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, 1983, quién enumera en detalle las modificaciones finales. Como dato curioso: desapareció de la versión final el nombre del vilipendiado poeta español Salvador de Madariaga.

[9] Véase la voz “Zukofsky, Louis (1904-1978)”, en: Adams, Stephen J./ Tryphonopoulos, Demetres P. (Editors); The Ezra Pound Encyclopedia, Greenwood Press, Westport, 2005, p. 309.

[10] Véase la voz “Bunting, Basil (1900–1985)”, en: ibidem, p. 22.

[11] La carta con la autointerpretación sobre GK en: Norman, Charles; Ezra Pound; Funk &Wagnalls, New York, 1968, p. 375.

[12] Los numerosos libros de prosa de Pound, algunos poco conocidos y agotados, son en orden cronológico: The Spirit of Romance (1910) Gaudier-Brzeska. A Memoir (1916), Pavannes and Divisions (1918), Instigations. . . Together with an Essay on the Chinese Written Character (1920), Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony (1924), How to Read (1931), ABC of Economics (1933), ABC of Reading (1934), Make It New (1934), Jefferson and/or Mussolini (1935), Social Credit: An Impact (1935), Polite Essays (1937), Guide to Kulchur (1938) y Literary Essays (ed. T. S. Eliot, 1954).

[13] Bacigalupo, Massimo. The Formed Trace: The Later Poetry of Ezra Pound, Columbia University Press, New York, 1980; Coyle, Michael; Ezra Pound, Popular Genres, and the Discourse of Culture, University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1995; Davie, Donald. Studies in Ezra Pound. Manchester, Carcanet, 1991; Lamberti, Elena; “’Guide to Kulchur’: la citazione tra sperimentazione modernista e costruzione del Nuovo Sapere”, en: Leitmotiv, 2, 2002, pp. 165-179; Lindberg, Kathryne V.; Reading Pound Reading: Modernism after Nietzsche, Oxford UP, New York:, 1987; Nicholls, Peter; Ezra Pound: Politics, Economics, and Writing: A Study of The Cantos, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1984. El rechazo in toto de la academia sería para Pound justamente un elogio indirecto a su método heterodoxo de aprendizaje y educación radicalmente revolucionario.

[14] Williams, William Carlos; “Penny Wise, Pound Foolish”, en: The New Republic, 49, 28, june, 1939, pp. 229-230. Williams llamaba en la recensión a Pound “a brave Man” por su honestidad intelectual y valentía política. La única crítica de Pound a Mussolini en GK es que en su mente todavía quedan residuos de Aristóteles: “… an Aristotelic residuum…”, e: Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 305.

[15] Pound los denomina nuclei, sus núcleos.

[16] Dice bellamente Pound: “La forma, el inmortal concetto, el concepto, la forma dinámica que es como el dibujo de la rosa hundido en las muertas limaduras de hierro por el imán, no por contacto material con el imán mismo, sino separado del imán. Separados por una capa de cristal, el polvo y las limaduras se levantan y se ponen en orden. Así la forma, el concepto resucita de la muerte.”, en: Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 166.

[17] Parataxis: se entiende como una construcción de dos oraciones sintácticamente independientes que están en una relación de subordinación implícita en virtud de lo que se conoce como una “curva melódica” común, que hace innecesario el uso de la conjunción, uniéndolas en una relación íntima de dependencia. Véase: Mounin, Georges (Dirigido por); Diccionario de Lingüística, Labor, Barcelona, 1979, p. 139-140. Estilísticamente puede decirse que mientras la hipotaxis (relación explícita mediante un signo funcional) señala un discurso meditado y racional, incluso de cierta “distinción” social en el nivel cultural de quién la emplea, la parataxis, propia de la expresión de emociones, es de un lenguaje más popular y llano. Pound: “The Homeric World, very human”, en: GK, p. 38.

[18] Además en GK se muestra claramente, como en Cantos, el milieu intelectual fascista en el cual se mueve Pound alrededor de los círculos romanos de Edmondo Rossoni, ministro de Agricultura del Duce y editor de la influyente revista cultural La Stirpe: “Eran personalidades serias, como las que Confucio, San Ambrosio o su Excelencia Edmondo Rossoni podrían y desearían reconocer como personalidades serias.”; en esta edición, vide infra, p. Sobre Pound y el Fascismo italiano, véase: Redman, Tim; Ezra Pound and Italian Fascism, Cambridge University Pres, Cambridge, 1991.

[19] Pound utiliza la palabra alemana Anschauung, un erkenntnistheoretischer Begriff introducido por Kant aunque ya utlizado por místicos como Notker o Meister Eckhart, para referirse a la superioridad epistemológica de la inducción y la intuición: “…la facultad que le permite a uno «ver» que dos líneas rectas no pueden encerrar una superficie, y que el triángulo es el más sencillo de todos los polígonos posibles.” Por ejemplo, el pedagogo iluminista Pestalozzi lo utilizó en un contexto operativo educativo, tal como pretende re-utilizarlo Pound. En esta revalorización de la Anschauung Pound aquí coincide no casualmente no sólo con Nietzsche sino con el neokantismo, Husserl y Heidegger, y en sus comentarios críticos a Aristóteles (Arry), Pound ubica a la intuición por encima de la sophia.

[20] Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 217.

[21] Pound dixit: “Bacon. No creo que la coincidencia con mis puntos de vista sea debida a memoria inconsciente, dos hombres en momentos diferentes pueden observar que los caniches tienen el pelo rizado sin necesidad de referirlo o derivarlo de una «autoridad» precedente.”

[22]Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 57.

[23] La Mostra… fue realizada con motivo del décimo aniversario de la Toma del Poder por Mussolini, tras la marcha fascista sobre Roma. Fue una idea de Dino Alfieri, futuro ministro de Cultura Popular. Pound visitó la Mostra… en diciembre de 1932, poco después de su inauguración oficial, quedando impresionado como la organización anti-museo Risorgimiento de iconografía, objetos cotidianos (el propio escritorio de Mussolini en el diario Il Popolo d’Italia) y collages de imágenes promovía la incitación del visitante a la acción. Sobre la Mostra… y su formato conservador-revolucionario, véase: Andreotti, Libero; “The Aesthetics of War: The Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution”, en: Journal of Architectural Education, 45.2, 1992, pp. 76-86; finalmente el trabajo de Jeffrey Schnapp: Anno X. La Mostra della Rivoluzione fascista del 1932: genesi-sviluppo-contesto culturale-storico-ricezione. With an afterword by Claudio Fogu, Piste – Piccola biblioteca di storia 4, Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali, Rome-Pisa, 2003 y su artículo: “Fascism’s Museum in Motion”; en: Journal of Architecture Education 45.2, 1992, pp. 87-97. Pound elogiará el aspecto radical y pedagógico de la Mostra… en su Cantos, el número XLVI, publicado en 1936. No es de extrañar: arquitectos liberales como Le Corbusier o un nietzscheano de izquierda como Georges Bataille también tuvieron una impresión profunda de la Mostra…

[24] Pound dice: “when one HAS ‘forgotten-what-book’ ” (GK 134) y más adelante: “what is left after man has forgotten all he set out to learn” (GK 195); véase: Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 151 y 197.

[25] Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 178.

[27] En GK, p. 34. Un ejemplo concreto de esta “limpieza directa” sería la obra de Gaudier-Brzeska.

[28] El famoso “Pound’s Pentagon”, su canon clásico y la superestructura cultural de un estado noble, lo constituye las Odas de Confucio, los Epos de Homero, la Metamorfosis de Ovidio, la Divina Comedia de Dante y las obras teatrales de Shakespeare.

[29] “El Comunismo como rebelión contra los ladrones de cosechas fue una tendencia admirable. Como revolucionario, me niego a aceptar una pretendida revolución que intenta inmovilizarse o moverse hacia atrás.”; en: Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 202.

[31]Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 78. No es casualidad que Pound indique formalmente al lector placentero del diario burgués típico.

[32] Pound había estudiado en detalle el método similar de sobreposición y parataxis que funciona en el Haiku japonés a través de los trabajos de Fenellosa.

[33] Pound, E.; “A Few Don’ts By an Imagiste”; en: Poetry, 1, 1916.

[34] “This book is not written for the over-fed. It is written for men who have not been able to afford a university education or for young men, whether or not threatened with universities, who want to know more at the age of fifty than I know today, and whom I might conceivably aid to that object.”, en: GK, p. 6.; en esta edición, vide infra, p. Pound consideraba, en una particular estadística personal, que en la sociedad burguesa podía encontrarse un lector reflexivo y serio por cada 900 lectores ingenuos o masificados.

[35] Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 57.

[36] Sobre el controversial antisemitismo ad hoc de Pound en GK, véase: Chace, William M.; The Political Identities of Ezra Pound & T. S. Eliot, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1973, Chapter Five, “A Guide to Culture: Antisemitism”, p. 71 y ss.

[37] “El genio de Mussolini era ver y afirmar repetidamente que había crisis no EN, sino DE sistema. Quiero decir que lo vio claro y temprano. Muchos lo vemos ahora.”

[38] “¿Y qué hay sobre anteriores guías a la Kulchur o Cultura? Considero que Platón y Plutarco podrían servir, que Herodoto sentó un precedente, que Montaigne ciertamente suministró una guía tal en sus ensayos, lo mismo que lo hizo Rabelais y que incluso Brantôme podría tomarse como una guía del gusto.”; en: Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 216.

[39] Dice Pound: “When the vortices of power and the vortices of culture coincide, you have an era of brilliance”.

[40] Pound en realidad llama a esta Océana ideal de su filosofía política Regime Corporativo.

[41] Pound, Ezra; Jefferson and/or Mussolini, Stanley Nott, New York, 1935, p. 96: “A good government is one that operates according to the best that is known and thought. And the best government is that which translates the best thought most speedily into action.”

[42] “The best Government is (naturally?) that which draws the best of the Nation’s intelligence into use.”, en: Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 266.

[44] Dice Pound: “Usury: A charge for the use of purchasing power, levied without regard to production; often without regard to the possibilities of production.” Es una conclusión extraída de las enseñanzas sobre el Social Credit del economista Douglas.

[45] En: Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 183.

[47] Pound nunca llegó a conocer los escritos juveniles de Marx, donde se analiza a fondo el papel del Dinero, por ejemplo.

[48] Amplias citas de Das Kapital en su obra The Cantos, en particular en el canto XXXIII.

[49] Véase el trabajo de Kathryine V. Lindberg: Reading Pound Reading: Modernism After Nietzsche, Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1987. Lindberg analiza la larga influencia del reaccionario pensamiento nietzscheano en la ideología y estética del Modernismo hasta el Postestructuralismo. De Gourmont recibió además Pound el impacto de la ideología derivada de Lamarck

[50] Pound, Ezra; “Redondillas, or Something of That Sort”, en: Ezra Pound: Poems and Translations, ed. by Richard Sieburth, Library of America, New York, 2003, pp. 175–182 (la stanza se encuentra en la p. 181). El poema “Redondillas…” es de mayo de 1911 y en él Pound también reconoce que lee a Nietzsche con la devoción con la que un cristiano se enfrenta a la sagrada Biblia.

[51] Pound, Ezra; “The Approach to Paris, III”, en: New Age, 13, Nº 21, 18 September 1913, pp. 607-609. Ahora en: Ezra Pound’s Poetry and Prose, 11 vols, Garland, London, 1991, I, C-95, pp. 156-159.

[52] Pound, Ezra; “Reflection”, en: Smart Set, 43, Nº 3, july, 1915, p. 395. Ahora en: Ezra Pound: Poems and Translations, ed. by Richard Sieburth, Library of America, New York, 2003, p. 1179.

[53] Sobre Nietzsche como pedagogo y reformador educativo, un aspecto infravalorado por los estudios y hagiografías, nos permitimos remitir al lector a nuestro libro: Nietzsche contra la Democracia, Montesinos, Mataró, 2010, capítulo V, “Pathein Mathein: la educación reaccionaria y ¿racista? del Futuro”, p. 173 y ss.

[54] Ezra Pound; Guía de la Kultura, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2011, p. 84.

Impresa ardua insegnare a qualcuno come leggerla, ma Pound è grande non solo per le sue opere maggiori, ma per l’incessante, ingenua volontà di regalare aiuto a tutti coloro che ne facciano richiesta. Il suo intento è quello di «offrire un manuale leggibile, tanto per diletto come per profitto, a chi non frequenta più le scuole, a chi non è mai stato a scuola, o infine a quanti ai tempi della loro istruzione hanno dovuto soffrire quello che hanno sofferto molti della mia generazione».

Impresa ardua insegnare a qualcuno come leggerla, ma Pound è grande non solo per le sue opere maggiori, ma per l’incessante, ingenua volontà di regalare aiuto a tutti coloro che ne facciano richiesta. Il suo intento è quello di «offrire un manuale leggibile, tanto per diletto come per profitto, a chi non frequenta più le scuole, a chi non è mai stato a scuola, o infine a quanti ai tempi della loro istruzione hanno dovuto soffrire quello che hanno sofferto molti della mia generazione».

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

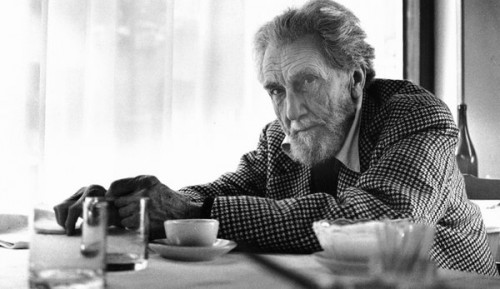

The answer he got bought him 12 years as a political prisoner in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Anacostia, just across the river from the Capitol in Washington D.C. Pound was never put on trial but was branded a traitor by the post-war American media.

The answer he got bought him 12 years as a political prisoner in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Anacostia, just across the river from the Capitol in Washington D.C. Pound was never put on trial but was branded a traitor by the post-war American media.

The liberty of subsidy

The liberty of subsidy